on

Verdure

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

An interesting report from the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies examined the “Use of digital health tools in Europe: before, during and after COVID-19“. Digital health is important not only because the technologies facilitate communication and disease monitoring, but also the technologies facilitate the creation of data that can be used to better improve health. Examples of digital health technologies include:

One key item of note was that use of digital health technologies prior to COVID-19 was highly heterogeneous across European countries.

While countries such as Estonia, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden were relatively advanced in terms of having implemented many digital health tools as well as having appropriate financial, legal and regulatory, and institutional frameworks for digital health in place, others, such as Poland, Germany and France, had lagged behind. Much unrealized potential for digital health remains in all European countries

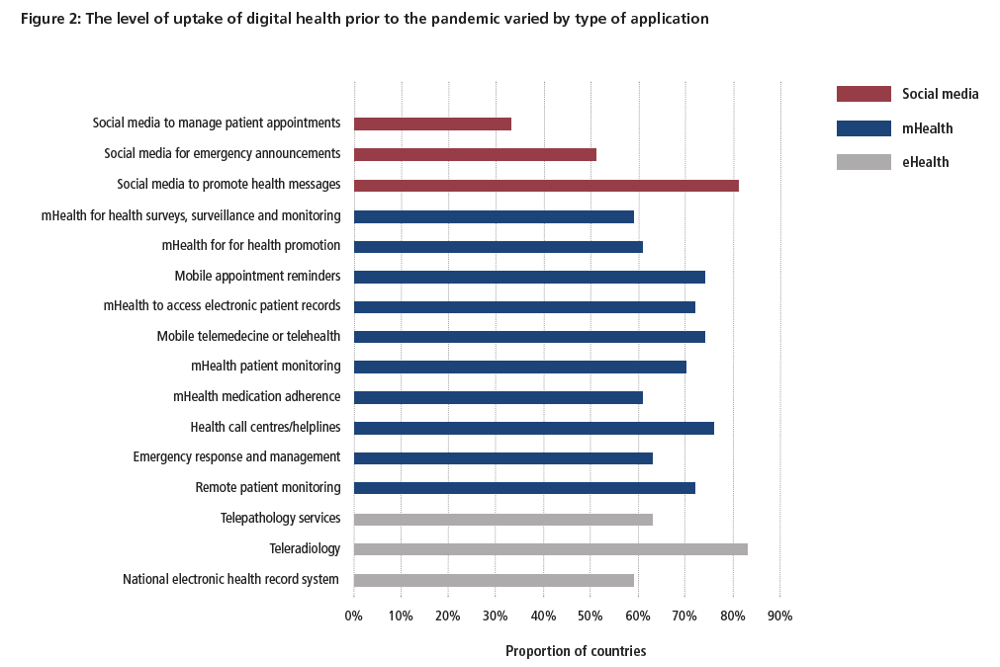

The figure below highlights the variability in uptake of digital health prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Note that many of the obstacles related to implementing digital health solutions were not technical, but rather systems based. Largely these barriers are legal and financial.

While some of the digital health tools used were novel (in particular contact-tracing apps), much of the underpinning technology that has been used during the pandemic already existed. At the system level, most actions to support the use of digital health tools during the pandemic have concerned the relaxation of limiting mechanisms, in particular the opening up of financing and reimbursement for these services where that was not already the case, and increased direct investment in digital health tools and the infrastructure to support them. How far regulatory limits have been addressed is less straightforward, with relatively little formal adaptation of regulatory frameworks for digital health tools.

Gaps in the current digital health regulatory framework are found across European countries:

Only 43% of reporting countries had policies or legislation defining medical jurisdiction, liability or reimbursement of eHealth services, 53% had no legislation allowing individuals to access their electronic health records, and just 13% had policies on regulating the use of big data in the health sector

Provider training on the use of digital health tools is also important, but the degree to which providers have been trained in the use of digital health tools is also highly heterogeneous across countries. While digital health is often beneficial to the average patient, its impact on health disparities is unclear.

Although digital health tools may help to address some kinds of inequality (such as enabling access for those who have difficulty in accessing local services), they can also create or exacerbate other inequalities (such as disparities in resources or skills to make use of new technologies).

Digital health was used during COVID-19 in a variety of ways. Most know that digital health was used for telemedicine, appointment scheduling, contact tracing, symptom reporting, vaccine adverse event monitoring, immunity certification (i.e., vaccine passports), hospital capacity management and in many other ways. However, few may be aware that digital technologies were also used in Ukraine to enforce quarantine at home mandates.

During the COVID-19 crisis, certain travellers arriving in Ukraine from abroad have been subjected to mandatory self-isolation (quarantine) for two weeks. The Ministry for Digital Transformation of Ukraine developed an app (‘Diy Vdoma’ – ‘Act at Home’) early in the pandemic in order to give people the option of isolating at home rather than undergoing a 14-day observation in a government-selected quarantine facility. To use the app, travellers must have a Ukrainian SIM card and have downloaded the app before passport control. At the border, guards send a code to the traveller’s phone to activate the app and link that individual to the phone number on the SIM card. The user then has 24 hours to reach their end destination and upon arrival there must enter their full name and address to confirm this as their place of self-isolation for the next 14 days.

Every day, at random, users’ phones receive around 10 notifications asking for a selfie, over 14 consecutive days; no notifications are sent at night. The selfie image is compared to the photograph taken at the border using facial recognition software, and the location where the selfie was taken is used to ensure that the user is still in quarantine.

Despite the progress made to date, future research is needed to more completely capture evidence on digital health’s cost and benefits of to society.

Comments

Post a Comment